JACOBUS O. SEYS, n1843.

Left College during Freshman year. 1839, Registered as from Liberia, Africa; son of Rev. John Seys, missionary. 1840, or thereabouts, sailed for Africa. Drowned in the harbor of Monrovia, soon after his arrival. Unmarried.

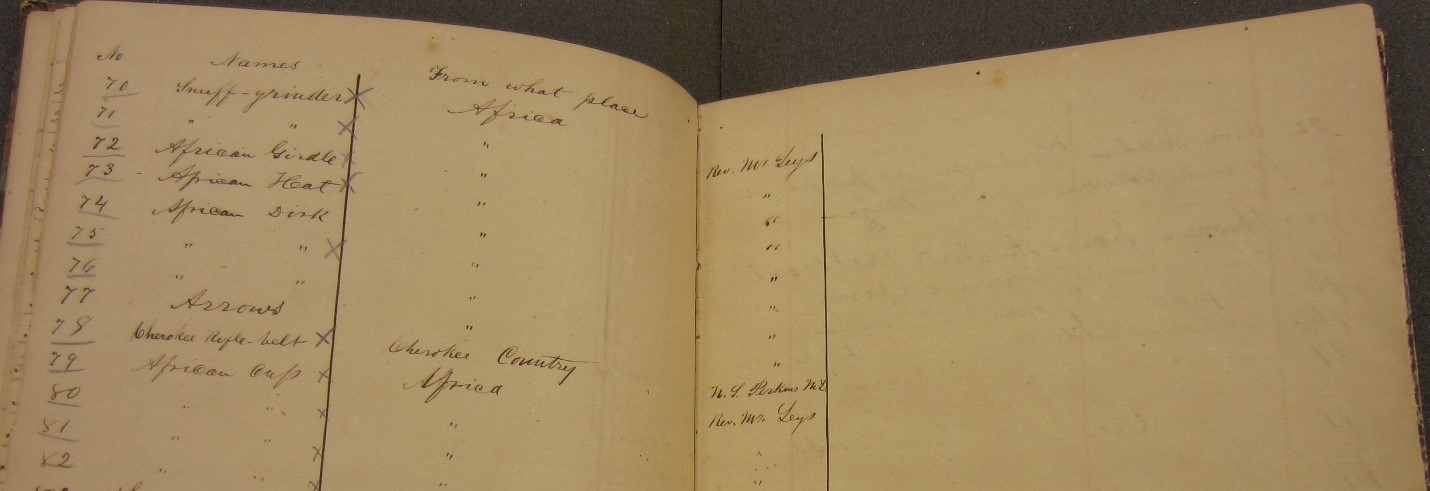

This grim entry in Wesleyan’s Alumni Record, published in 1883, offers a sad glimpse into the tangled web of Wesleyan’s early connections with Africa. Read in context with the Missionary Lyceum logbook (“Curiosities belonging to the Missionary Lyceum”) pictured above, inventories from the Archaeology & Anthropology Collection, correspondence in President Willbur Fisk’s Papers, and other sources, we can piece together a network of personal relationships and events that likely led to Wesleyan’s holding one of the largest groups of pre-1850 cultural objects from Monrovia, Liberia, in an American collection. The collection of more than 40 items, including domestic and religious objects, ceremonial clothing, and other items, offers many possibilities for research. It was given to Wesleyan’s first student organization, the Missionary Lyceum, by Rev. John Seys, a Methodist missionary who later became the first U.S. ambassador to Liberia. Today it is part of Wesleyan’s Archaeology & Anthropology Collection; the records of the Missionary Lyceum are held by Special Collections & Archives.

Liberia, the West African country founded in the 1820s by free people of color from the United States, had close ties to the American Colonization Society. The Society organized and funded emigration to Liberia in an attempt to ameliorate the evils of slavery in the U.S. The colonization movement had supporters among Wesleyan’s earliest administration and faculty, including President Willbur Fisk and professor of ancient languages Daniel Whedon. Rev. Seys corresponded with Fisk about his missionary travel to Africa, and Fisk helped him find a place to live when he came to Middletown.

Both Fisk and Whedon were also members of the Missionary Lyceum. Members of the group of students, faculty, and local men who served (or hoped to serve) as missionaries corresponded with other missionaries around the globe. As early as 1834, they were soliciting donations of “African curiosities” for a missionary museum. By 1837 they had established a library of books to support missionary work, including translations of the Bible into 81 languages. When Mary Seys, the wife of Rev. Seys, died, the Missionary Lyceum arranged for a monument in her memory.

Wesleyan’s first black graduate, Wilbur Fisk Burns (Class of 1860), also came to Middletown from Liberia. The namesake of President Fisk, Burns was the son of Bishop Francis Burns, the first Missionary Bishop in Liberia and, later, the first African American Bishop in the Methodist Episcopal church. Bishop Burns was a friend and political ally of Rev. Seys. The younger Burns returned to Liberia after graduation and served in the government.

The records of exactly when, where, how, and from whom the African objects in the Missionary Lyceum museum were acquired are murky at best, and they raise more questions than we have answers. The blank areas in the Missionary Lyceum logbook highlight how little was recorded. How did Rev. Seys come by these items? Were they given to him willingly or confiscated? Did money or valuable goods change hands? Did the Liberians know that their cultural objects were given to a missionary collection in America?

This blog post is fifth in a series on ephemera in Wesleyan’s Special Collections & Archives, presented in conjunction with the Center for the Humanities’ Spring 2021 theme of Ephemera. Special thanks to Wendi Field Murray, Collection Manager for the Archaeology & Anthropology and East Asian Art & Archival Collections, for her help with this post. On March15th at 6 p.m., CHUM Mellon Postdoctoral Fellow Mlondolozi Zondi (will lecture on “Performance and the Ownership of African Things.” Here is the full series calendar.

– Suzy Taraba, Director of Special Collections & Archives