Literary commonplace books flourished in Europe in the 17th and 18th centuries. Compilations of excerpts from beloved, meaningful, or thought-provoking texts, typical literary commonplace books like this one offer a window into the reading habits of their makers. Centuries before Pinterest promoted gathering visual images to be organized, saved, and returned to again and again, handwritten commonplace books performed a similar function for preserving special passages without having to reread an entire text. Each commonplace book is different, of course, but most include no original writing. The uniqueness lies in the passages chosen and the way they are organized. Copying out excerpts serves as an aide-memoire, uniting the intellectual and emotional pleasures of a favorite quotation with the muscle memory of writing it out by hand. Body and mind are united and connected to literature.

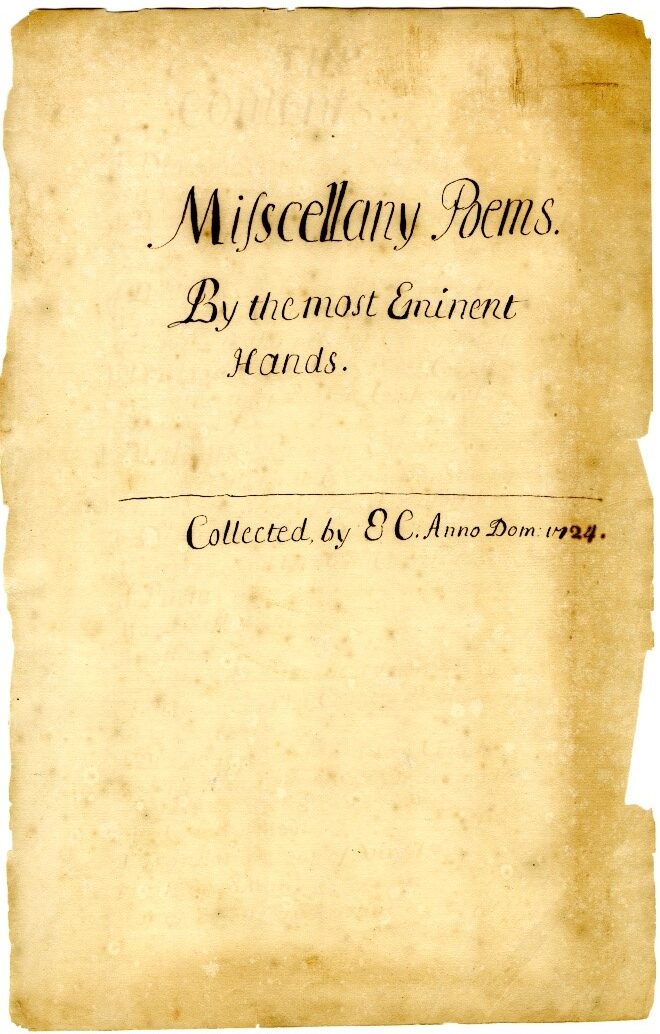

It’s that process, the total involvement of a person with the reading of literature, that’s the ephemeral aspect of a commonplace book. The experience is fleeting, though it can be recreated. The object itself is large and heavy: a substantial, leather-bound folio volume, comprising 364 pages with excerpts from 95 separate texts listed on four pages of the table of contents. English authors abound, with some well-placed English translations of classical authors. Congreve, Prior, Pope, and Charles Dryden – son of the more famous John – are prominent. Horace is a favorite among the classics. Common themes include heaven, hell, friendship, death, morning, and darkness. At least nine of the entries are selections from dialogues, some quite lengthy, and some featuring female characters. A significant number of texts are presented anonymously. Strategic searching in electronic resources such as Early English Books Online will readily reveal the authorship of most of these entries. Less likely to be unmasked is the commonplace book’s compiler. Identified only by the initials E.C. and the date 1724, the possibilities are endless, and the quest to identify precisely may well be futile.

E.C.’s Misscellany Poems found its way to Wesleyan’s Special Collections & Archives in 2000, along with several boxes of materials transferred from Wesleyan’s museum collections. The commonplace book had never been formally accessioned or cataloged. A faint pencil note on a scrap of paper with the book identifies it as having been donated by Randolph S. Lyon, 163 Mt. Vernon St. Unrelated printing on the verso of that scrap indicates that the donation occurred after 1932. The connection between Mr. Lyon and the author of the commonplace book, if any, is a mystery. Someone along the way – perhaps Mr. Lyon, perhaps another reader – left behind a bit of evidence of engagement with the commonplace book. Tucked between pages 159 and 160 is a tiny clipping, most likely from a 19th century newspaper. The scrap bears the text of a poem, “I can never forget thee.”

This blog post is second in a series on ephemera in Wesleyan’s Special Collections & Archives, presented in conjunction with the Center for the Humanities’ Spring 2021 theme of Ephemera. On February 22nd at 6 p.m., CHUM fellow Michael Meere will lecture on “(Un)Popular Performances in Early Seventeenth-Century France.” Here is the full series calendar.

– Suzy Taraba, Director of Special Collections & Archives