By Oliver Egger, Class of 2023

Shut Not Your Doors to Me Proud Libraries

By Walt Whitman

Shut not your doors to me, proud libraries,

For that which was lacking among you all, yet needed most,

I bring; A book I have made for your dear sake, O soldiers,

And for you, O soul of man, and you, love of comrades;

The words of my book nothing, the life of it everything;

A book separate, not linked with the rest, nor felt by the intellect;

But you will feel every word, O Libertad! armed Libertad!

It shall pass by the intellect to swim the sea, the air,

With joy with you, O soul of man.

It was two years ago, April of 2019, that I first came to the Special Collections and Archives. I was a pre-frosh at WesFest, awkwardly wandering across campus with a wrinkled assortment of info sheets and campus maps. The disorienting stream of events and people left me with a nagging sense of worry: maybe Wesleyan wasn’t the place for me, maybe it was all too much.

I bumbled into Olin on a library tour, hoping walking up those massive stone steps would make me feel more put together. I joined the tour group as the librarian pointed out the way the printers worked and the infamous nap pods. I quickly peeled off into the hallway towards the exit. Out of the corner of my eye, I was drawn to glass doors with the words Special Collections and Archives on them. I took a deep breath and then stepped inside, my first introduction to a space that would open itself up to me, full of words and treasures.

Suzy Taraba, the director of special collections, was sitting at the main desk, a wooden shelf dotted with ancient-looking books and trophies rising behind her. We started talking right away and I asked her about SC&A and her role. I soon found out she was a Wesleyan alum and even lived in my hometown in North Carolina for a period, living only a few streets from where I grew up. “What kind of books do you have here?” I asked, trying to read the faded red and gold-lettering on the sea of books billowing behind Suzy.

“What kind of books are you interested in?” she responded.

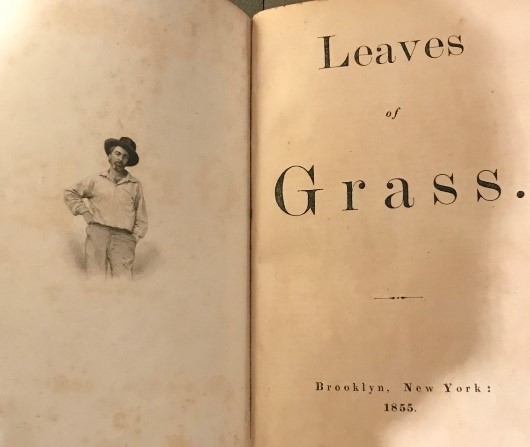

“Poetry mainly,” I said. “Do you have any, uh, old copies of Whitman?” I asked, thinking of the faded portrait of the white-bearded bard my dad has hanging above his desk and the dog-eared paperback of Leaves of Grass sitting somewhere in my backpack. She smiled and told me that Wesleyan had a large collection of Whitman, including the rare 1855 first edition that Whitman essentially self-published.

“Come by tomorrow and I can show it to you,” she said. “And some other things as well.” We found a time and the next day, with my friend Lucie from home who was considering Wesleyan, I met Suzy in the Davison Rare Book Room. On the dark wooden table were various editions of Walt Whitman’s masterpiece laying on foam book-beds. I walked over, past the massive ornate globe and stared at the pages of poetry, preserved through time to reach me in that moment.

Whitman published six editions of Leaves of Grass in his lifetime; the central poem took on various titles from “Leaves of Grass” (1855) to “Poem of Walt Whitman, an American” (1856), to “Walt Whitman” (1860), until he finally he settled on “Song of Myself” in the last edition (1891–2). In each edition, the poetry changes slightly; new stanzas and different word choices appear on the aged brown paper.

The images of Whitman change too: from Brooklyn thirty-year old handsomely leaning with a hand on his hip to the white bearded sage that presided over my dad’s office.

As the words and Whitman himself change, we, the reader, change with him. The atoms in him belong to us as well. “It is you talking just as much as myself… I act as the tongue of you.”

When I read Whitman, it is not hard to feel as though his words were written yesterday, his barbaric yawp echoing for the first time across the rooftops of the world. Coming face to face with the book in that moment, my hands lifting the wrinkled pages, opening the delicate cover of the first edition, where roots spring off the bottom of the letters, I felt that sense of connection more than ever. That magic of recognizing yourself in the past is something poetry and the archive can achieve. I thanked Suzy for her kindness and boundless knowledge, then left the library that afternoon, the sun streaming down those collegiate steps, feeling seen and a little bit less worried.

Two years after that moment, we are again in April, another poetry month, in a very different world. The spontaneity of my discovery that day, where I met a mentor and was able to come face to face with a poem that means the world to me, is harder to come upon now. Who could have guessed that the 2019 WesFest would be the last in-person one for (at least) two years? The way I view Walt Whitman and his exaltation of America has shifted as well, he too is a flawed figure of history. The way I even view what college looks like has changed. What is the collegiate experience in the midst of this tiring and disconnecting pandemic?

At the start of this piece, I included one of my favorite Walt Whitman poems: Shut Not Your Doors to Me Proud Libraries. On one level I included it because it seemed a fitting choice for a piece about my connection to the library, but beyond that I believe it says something fundamental about what poetry can be in this year and in years to come. In many people’s eyes, poetry is surrounded by an impenetrable wall of intellectualism. In my humble, and indeed biased opinion, poetry in its finest form, as Whitman alludes to in this piece, is not a fortress to be feared but an accessible celebration of the joy of life. When you read the words of a poet you connect with, whether it’s Sappho or Jericho Brown, life blooms off of the pages. Maybe, like me, you are far away from the Special Collections and Archives, and can’t make an appointment to see the 1855 Leaves of Grass or whatever your favorite equivalent poetry book is. But what poetry does is to remind you that beauty and life exists all around, beyond a single place: it lives in the sea and in the air and within you. This year has taken away a lot, and sometimes I roll my eyes when I hear these messages of hope and connection, but they do exist; they live in corners of poetry books and in the old wooden reading rooms at Wesleyan.

If you’re at Wesleyan today make an appointment and the SC&A will open its doors to you, if you’re not at Wesleyan find a poem you love and if it’s right, no matter the world’s weight or where you are, it, too, will open itself to you.