This guest post for World Day for Audiovisual Heritage was written by Stuart Wheeler, MA ‘21, who has spent the past several months working with the World Music Archives as well as Special Collections & Archives to help process collections from contemporary American composers including John Cage and Ned Sublette. One of his projects was working with the New American Radio collection in the World Music Archives, and we asked him to tell us about what he found.

Find out more about The New American Radio collection at www.somewhere.org.

– Aaron Bittel, Director, World Music Archives

American Radio Art at the End of the Millenium

Of all the various media developed for disseminating sound in the last century, radio has been the most enduring presence. The artist Jacki Apple wrote that radio “is the bridge between the two halves of the 20th century . . . . For three decades radio held a central place in our living rooms . . . . Still, for another two decades it was a primary conduit for youth culture and its music—rock’n’roll.”1 Artists and composers began using radios in their work quite early. In 1942 John Cage composed his first piece which involved a radio—Credo in Us—and continued to compose a number of others in the ensuing decades which made use of radios as indeterminate sound-elements. Cage once joked to his friend and fellow composer Morton Feldman that he was no longer bothered by hearing everyone’s individual radios playing at the beach: “Now, whenever I hear radios . . . I think, ‘well, they’re just playing my piece.'”2 Still, as Apple points out, it was not really until the 1980s that avant-garde artists began to be able to consistently infiltrate pockets of the radio’s actual airwaves. This new space opened up as the confluence of new developments in accessible recording and broadcast technology, along with the establishment of non-commercial college and community radio stations.

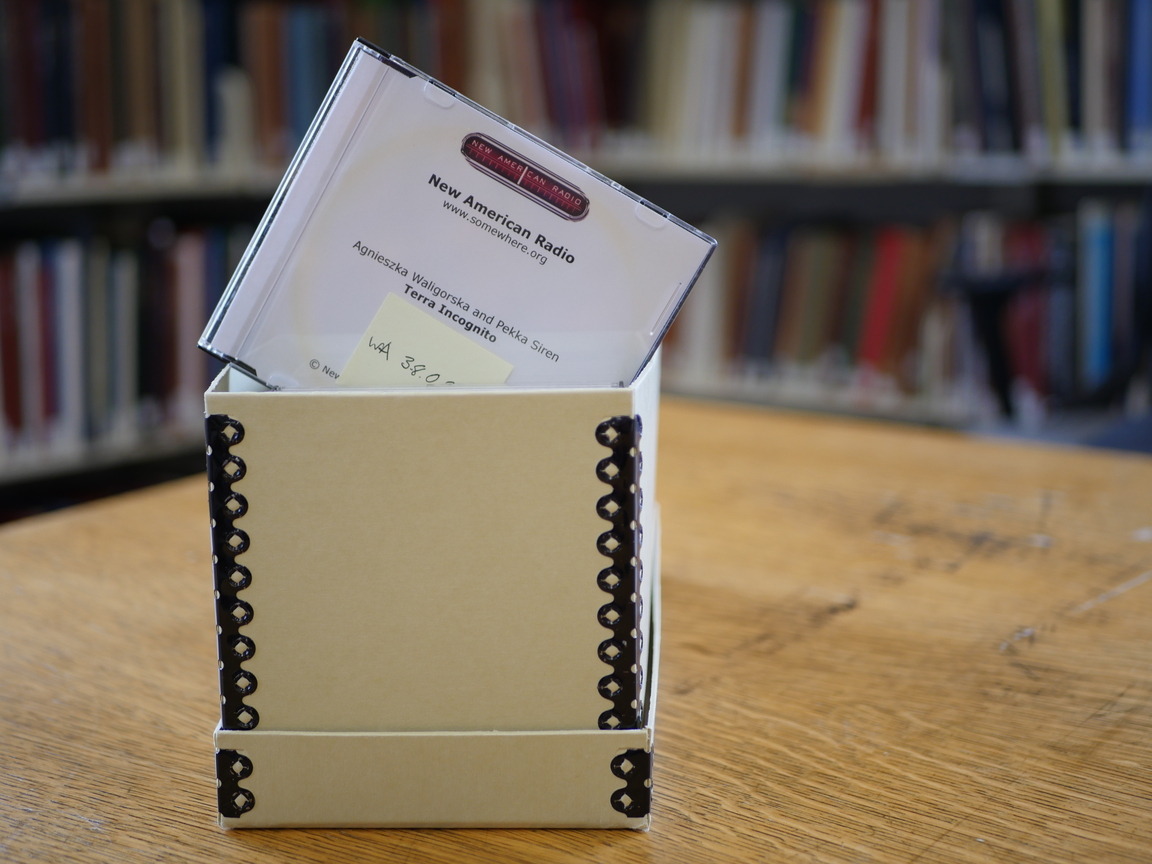

New Radio and Performing Arts, Inc. (NRPA)—founded in 1981 by Helen Thorington—and its New American Radio (NAR) series became one of the most significant commissioning organizations for experimental radio art in this period. From 1987 to 1998, NAR ran weekly programs of art works made exclusively for radio. These works spanned a diverse field: psychoacoustic drama, documentary, radio plays and cinema, musique concrete, and multimedia performance art. Though its funding to commission new work ran out at the end of the 1990s, NAR’s catalogue is now archived both online—at somewhere.org—and physically—as part of Wesleyan’s World Music Archives. These archives offer a wide look into the type of work that was being made by sound artists for radio in the final decade of the previous millenium. Below I will give a sampling of a few different kinds of work included in the collection. All these examples and many others can be listened to online at somewhere.org.

One of the more straightforward pieces in the collection is the hauntingly surreal radio play Hunger (1989), by acclaimed Cuban-American playwright Maria Irene Fornes. Making use of a minimal sound score, the work relies primarily on sparse, stilted dialogue to assemble a disorienting and bleak vision of the future. This one-act play was Fornes’s first commission for radio, adapted from her larger collection for the stage And What of the Night? (1989), which tells the sprawling story of a single family through four separate one-act plays.

Two quite different approaches to constructing a sonic scene can be found in works by composer and sound artist Hildegard Westerkamp and New American Radio founder Helen Thorington. In Cricket Voice (1987), Westerkamp took as her core a recording of a cricket she made in a desert region of Mexico popularly known as the Mapimí Silent Zone. Throughout the piece, she sped up and slowed down the cricket’s song, adding to it percussive sounds she made on desert plants and an old abandoned water reservoir. Thorington’s short One to Win (1989), on the other hand, whips the listener around with hard cuts, sudden changes in perspective and incessant repetition. Gradually the sonic fragments begin to form a strangely cohesive day at the racetrack, following a horse named Cold Spot.

This accumulation of disparate sounds into a larger sonic geography is attempted on a more ambitious scale in Joseph Celli and Jin Hi Kim’s World Soundprint: Pacific (1993). Celli and Kim collaged together a wide variety of recordings the two musicians had made during their travels through a number of Asian countries. The sounds range from the overtly musical to the mundane. The composer John Luther Adams attempted a similar undertaking in his New American Radio commission Earth and the Great Weather (1990), representing a sonic imprint of the Arctic National Wildlife Refuge in Alaska. Adams took a less documentarian method, combining recordings made of indigenous Inupiaq drumming and singing with high floating tones from an Aeolian harp, field recordings of environmental and animal sound, and composed words in English, Latin, and Inupiaq. Adams’s piece draws attention directly to languages and their sound, seeming to suggest that they represent a significant part of any place’s sonic geography.

Other artists used found sounds and language to explore different types of non-geographic space. In A Beginner’s Guide to Attracting Birds (1995), composer Alvin Curran constructed certain types of what he calls “acoustic spaces” by manipulating field recordings so that they gradually blend into speech.3 Particularly notable is the occasional emergence of the voice of composer John Cage, who had died a few years before Curran made this piece. Composer/performer Pamela Z’s Parts of Speech (1995), on the other hand, articulates the social spaces enforced through our linguistic constructions. Part lecture, part poem, part music, Z’s piece uses found and composed text to demonstrate ways in which language can be used to act upon others, to aggress and to dehumanize, while at the same time exposing the nonsense that stitches all our language together.

Some of the works in the collection blend journalism with meticulous sonic structures. Ron Kuivila’s Hearing Things (1991) is a good example, as is Bob Ostertag’s devastating Sooner or Later (1991). Kuivila’s piece threads together a number of interviews and sounds, all apparently related only by the loose theme that each interview is addressing — some topic of hearing, or non-hearing. Interview topics include one interviewee’s personal history with perfect pitch, theories of the evolutionary biology of hearing, age demographics of radio listening by genre, and the effect of sound below the level of human hearing, to name a few. The distinct interviews are chopped up into segments of differing lengths which alternate, returning and repeating in various patterns. Ostertag’s piece samples a short recording of a young boy crying as he buries his dead father. The recording was made while Ostertag lived in El Salvador, working as a journalist and political activist during the country’s Civil War. He said the following about the work: “There is a boy and his father is dead. And no angels sang and no one was better because of it and all that is left is this kid and the shovel digging the grave and a fly buzzing in the air. If there is beauty, we must find it in what is really there: the boy, the shovel, the fly. If we look closely, despite the unbearable sadness, we will discover it.”4

Ned Sublette’s The Auctioneer (1989) takes a less abstracted approach to sonic journalism and interview. Sublette spent two weeks attending the Missouri Auction School in Kansas City. His piece splices together an assortment of recordings made from teachers speaking, attendees doing drills together and separately, as well as interviews with attendees giving their respective stories for how they decided to attend the school. More than anything, Sublette’s finished product draws attention to the deeply musical quality of an auctioneer’s vocalizations. In an interview he gave about the making of the piece, Sublette explained that he “saw it less as a documentary and more as a musical composition.”5 When asked which sonic experience from the two-week course stuck with him the most, he replied: “The drills. Seventy-five men and women, mostly from Missouri, Kansas, and Arkansas, chanting numbers together at eight in the morning. It was tantric. I imagined Philip Glass hearing it in his dreams.”

The art critic Claire Barliant has raised questions of how the work commissioned by NAR changes when it moves from time-based radio as its medium to a permanent archive housed on the internet. “Part of the appeal,” she writes, “of art made for radio is in the tension created when an experimental artist tries to subvert the medium’s mainstream status while simultaneously leveraging its capacity to reach a wide audience.”6 While the medium of internet provides some parallels to the mass accessibility of radio, the information flow and sociality of it could hardly be more different. Barliant’s question will only be possible to answer in time, as new and future generations engage with the work as historical media.

– Stuart Wheeler, MA ‘21

Of note: Jin Hi Kim is Director of the Korean Drumming Ensemble and Adjunct Assistant Professor of East Asian Studies in the College of East Asian Studies at Wesleyan. Ron Kuivila ‘77 is Professor of Music.

________________________________________

- Apple, Jacki. New American Radio and Radio Art.

http://www.somewhere.org/writings/apple.htm - Cage, John and Morton Feldman. Conversations.

https://blog.wfmu.org/freeform/2005/02/john_cage_morto.html - Curran, Alvin. A Beginner’s Guide to Attracting Birds.

- Ostertag, Bob. Sooner or Later.

- Sublette, Ned. Behind the Scenes pt 1.

https://www.thirdcoastfestival.org/article/behind-the-scenes-pt-1-with-ned-sublette - Barliant, Claire. Stationary Flow: Process and Politics in Audio Art On the Air and Online.

http://www.somewhere.org/writings/barliant.htm