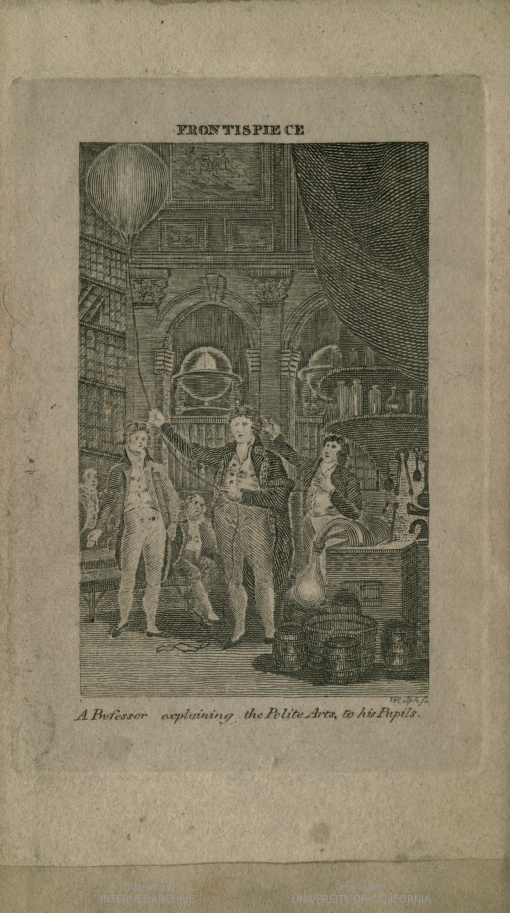

Enlightenment ideas about science and philosophy take center stage in this small book of lectures presented to children by a boy called Tom Telescope, the “little philosopher.” The pseudonymous Tom explains complex concepts through conversation and demonstration with “familiar objects, in an entertaining manner, for the use of young ladies and gentlemen,” as made clear in the publication’s subtitle. Tom covers matter and motion, the universe, natural phenomena, minerals, vegetables, animals, and man, culminating in a discussion of human understanding. The other children question Tom, sometimes challenging his assertions. Tom answers with equanimity, offering more examples to help juvenile comprehension.

Tom Telescope’s foray into Newtonian philosophy is a convergence of widespread dissemination of intellectual ideas and the development of a robust market in books for children. John Newbery, the mid-18th-century London publisher and purveyor of patent medicines, was the first to make publications for young people a central part of his business. Others before him had put forth occasional titles, but no one fully developed the market before Newbery. Today the American Library Association’s award for the best works for children is named for Newbery.

Newbery may have written Tom Telescope’s work himself, although it has sometimes been attributed to Oliver Goldsmith, the Anglo-Irish novelist, playwright, and poet, who was Newbery’s most prominent author. Whoever wrote it, the text was very popular from its initial publication in 1761 until well into the 19th century. Numerous editions were issued in England and the United States, along with translations into several European languages. The text itself proved quite elastic, with expansions to accommodate new scientific discoveries and a shift in Tom’s audience of children from the nobility and upper classes to include young people from the middle classes. Tom himself aged to become a well-educated young man rather than a child prodigy.

Special Collections & Archives holds the 1808 edition of The Newtonian System, which was published in Philadelphia in 1808 by Johnson & Warner and printed by Lydia Bailey. It features additions and notes by Robert Patterson, a professor of mathematics at the University of Pennsylvania. This edition and several others are also available digitally.

Our copy once belonged to Charlotte Rosella McDonough, who was born and raised in Middletown. Charlotte was the daughter of Lucy Ann Shaler and Commodore Thomas Macdonough, Jr., well known for his roles in the first Barbary War and the War of 1812. Charlotte Macdonough married Henry Griswold Hubbard, a scion of one of Middletown’s founding families. The book came to Wesleyan’s library in 1878 as part of the extensive bequest of Jacob F. Huber (1801-1878), Wesleyan’s first professor of modern languages.

This blog post is tenth in a series on ephemera in Wesleyan’s Special Collections & Archives, presented in conjunction with the Center for the Humanities’ Spring 2021 theme of Ephemera. On May 3rd at 6 p.m., Daniel Smyth (Wesleyan) will lecture on “In the Blink of an Idea: Infinitesimal Calculus and the 18th Century Mind.” Here is the full series calendar.

Suzy Taraba, Director of Special Collections & Archives