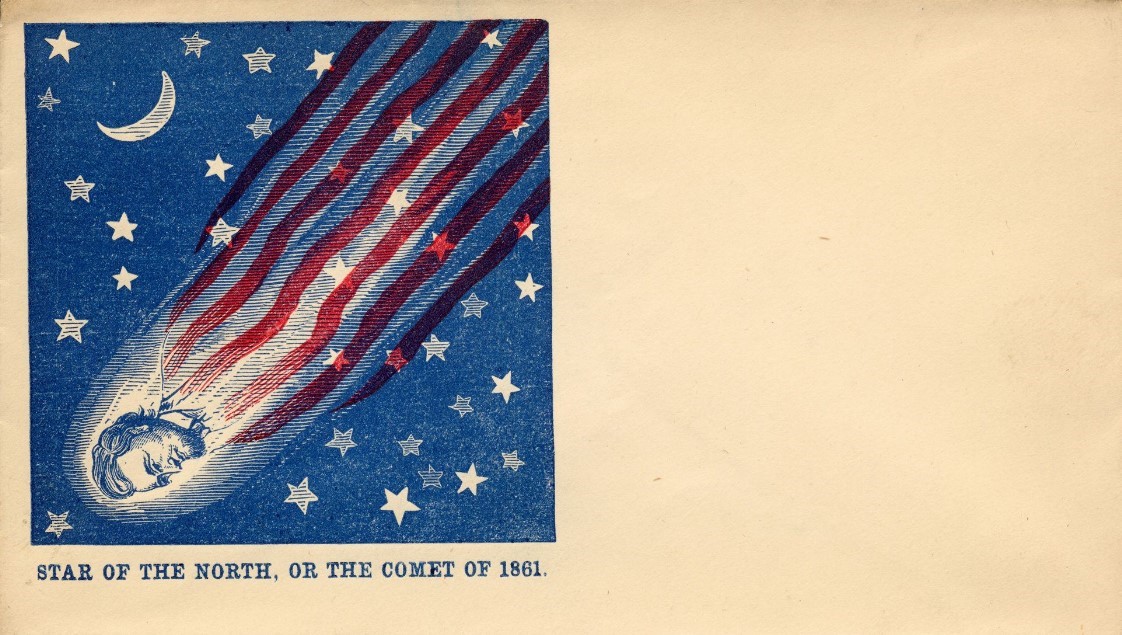

This graphically arresting envelope depicts President Abraham Lincoln as the Great Comet of 1861, which could be seen with the naked eye throughout the summer in much of the United States. The anonymous illustrator has combined several visual elements to create greater meanings: the white stars on a blue background representing both the heavens and the American flag, the red stripes evoking both the Union and the tail of the comet, the familiar visage of the incumbent president coming to the rescue or hurtling toward his doom. Which would it be? At the beginning of the war, when this envelope was produced, no one knew.

Throughout history, comets have been viewed by some as omens, portents of cataclysmic change or disaster. The Great Comet of 1861 was seen by some – both at the time and in retrospect – as an allegory of the Civil War. Soldiers and civilians wrote about seeing it overhead, remarking on its meaning. A brief article in the Hartford Courant on July 1, 1861, makes the connection between ancient beliefs and the contemporary war: “Superstition of heathen or medaeival ages might see in it the avenging sword of the deity of the North …”

Illustrated envelopes with themes emphasizing the divisions between the North and the South were printed in many U.S. cities as early as the mid-1850s, and they became ubiquitous in the early years of the war. Although this patriotic stationery was originally intended for postal use, it quickly became a collectible commodity. Only a modest percentage of the surviving examples shows evidence of writing, postmarks, or stamps. Instead, they were carefully preserved as a record of popular ephemera of their day. Collectors ensured their survival and their amassing into groups, opening a window into the vernacular iconography of the time. Envelopes printed in the Northern states predominate by a wide margin, but there are Southern examples, too. Not surprisingly, due to the paper shortages and other far more dire exigencies of war, the Southern envelopes are both scarcer and rougher. And yet they were printed, and some of them survived.

The Lincoln comet postal cover, printed in 1861 in Philadelphia by Samuel C. Upham, is part of a collection of thirty-six Civil War-era pictorial envelopes donated in the early 2010s to Special Collections & Archives by Barry and JoAnne Scott, Rhode Island rare book dealers and friends of SC&A. The collection includes a wide array of images, from the modest blue logo of the Hartford Wide Awake Party to elaborate cartoons lampooning Confederate President Jefferson Davis to a multicolored, lithographed “camp scene” depicting ten soldiers and sailors in various uniforms, printed in New York by Charles Magnus “from a photograph.”

The Scott gift complements an album of 143 similar envelopes already in SC&A. The album bears the bookplate of the Odell Alcove, a collection of American history materials established in Wesleyan’s library not long after the end of the Civil War and named in honor of Representative Moses F. Odell, a Congressman from New York. The variety of illustrated Civil War era stationery produced was so great – literally thousands of designs – that there is very little duplication among the 179 postal covers held by SC&A. Fuller information about each collection can be found in the library’s catalog here and here.

This blog post is the first in a series on ephemera in Wesleyan’s Special Collections & Archives, presented in conjunction with the Center for the Humanities’ Spring 2021 theme of Ephemera. On February 15th at 6 p.m., CHUM fellow Marina Bilbija will lecture on “Black Comet Literatures: Reading for the Ephemeral Literary Histories of Pan-Africanism.” Here is the full series calendar.

– Suzy Taraba, Director of Special Collections & Archives