This month marks thirty years since the passage of the Native American Graves Protection and Repatriation Act, also known as NAGPRA. NAGPRA is a federal law that protects Native American graves and funerary objects. It also provides a process by which museums and agencies must repatriate Native American human remains, funerary objects, and certain categories of cultural objects to lineal descendants, Native American tribes, and Native Hawaiian Organizations.

You may have questions about this already – from what or whom did Native American graves and objects need protecting? Why was this passed only 30 years ago? And what does it have to do with Wesleyan? Let’s start with the first…

Why Did Native American Graves and Cultural Objects Need Protecting?

When anthropology was in its infancy, its practitioners subscribed to social evolutionary theories of human development. The primary aim of social scientists during the 19th century was to establish racial classification schemes and rankings, to better understand differences between human populations. But this line of questioning was undergirded by colonial assumptions of white superiority, and served to justify attitudes and policies that dispossessed indigenous peoples of their lands, sovereignty, and religious freedoms. By studying indigenous bodies and collecting Native American objects, anthropologists (including archaeologists) sought to salvage what information they could about this “vanishing race” before it was too late. [i]

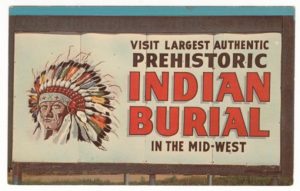

Native American burials were viewed as easily accessible source of “data” that could support this research. Once taken, they remained in museum collections to be studied, and their identities were secularized as artifacts[ii] – anything associated with indigeneity was viewed as a relic of America’s past. There was little effort to understand the psychological and spiritual harm that these practices and attitudes inflicted upon contemporary indigenous communities who had not, in fact, vanished. By the time NAGPRA was passed, it is estimated that museums across the country held the remains of more than 200,000 Native American ancestors, and more than one million funerary objects.[iii]

Why Was This Law Passed Only 30 Years Ago?

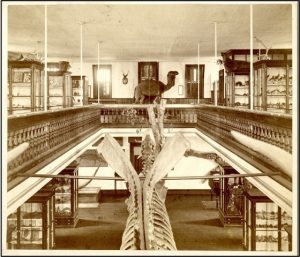

As early as the 1880s, indigenous peoples have been fighting to recover and rebury their ancestors and to gain access to their ceremonial objects. But without repatriation legislation, they had no legal recourse for doing so. And even as 19th-century social theories were replaced by others, indigenous human remains, funerary objects, and ceremonial objects remained in museums, under the physical control and intellectual authority of non-indigenous peoples. Like military buttons or historical ceramics, ancestors sat on museum shelves in service to Western science, and for the benefit and enjoyment of the general public through exhibits and displays.

In the United States, the repatriation movement emerged from the civil rights movement, and sought redress for these injustices. It became more organized during the 1980s, as indigenous activists and advocates began working with members of Congress to draft a bill. There was considerable pushback from the scientific and museum communities, some of whom felt that the law stymied scientific inquiry and feared that museums would be emptied of their collections. On November 16, 1990, the Native American Graves Protection and Repatriation Act was signed into law.

What Does NAGPRA Have to Do with Wesleyan?

Wesleyan University has NAGPRA obligations because it meets the law’s definition of a museum.[1] The Wesleyan Museum was established in 1871 and was housed on the top two floors of the Orange Judd building. Wesleyan was a collecting institution almost from the start, and until the mid 20th century, actively sought out and acquired objects of natural and cultural significance from around the world, including those of Native American origin.

Though the museum was disassembled in 1957, the collections remain under the care of the university. At one time, Wesleyan also cared for the remains of 15 Native American ancestors. This is, unfortunately, not unusual – Wesleyan is one among many universities who built collections during the 19th century to support their science programs, and to build status and prestige in the academic community. These institutions did not all necessarily seek out human remains, but would often accept them as donations from private collectors.

NAGPRA gave museums five years to comply. At the time, Wesleyan did not have staff or resources dedicated to the fulfillment of all NAGPRA obligations. Repatriation advocates on campus are credited with educating our community about the scope of our NAGPRA responsibilities, and ensuring that our institution demonstrated a commitment to this work. Ten ancestors were repatriated in 2014, and I will spend the next year working with local tribes toward the repatriation of the remaining five ancestors in our care. I will also be working on making our collections easily searchable so that Native American tribes and Native Hawaiian Organizations can get a better sense of what types of objects are in the collection, and whether they are interested in further consultation.

At its core, NAGPRA is human rights legislation. It is far from perfect – three decades after its passage, more than 100,000 ancestors are still held in museums across the country. But NAGPRA’s ripple effects have been widespread, and there are reasons to believe that things have begun moving in the right direction. What is accomplished over the next 30 years will be up to all of us.

– Wendi Field Murray, Archaeology Collections Manager/Repatriation Coordinator

[1] Any institution or State or local government agency (including any institution of higher learning) that receives Federal funds and has possession of, or control over, Native American cultural items [25 USC 3001 (8)].

[i] Thomas, David Hurst. 2000. Skull Wars: Kennewick Man, Archaeology, and the Battle for Native American Identity. Basic Books, New York, NY.

[ii] Bieder, Robert E. 2000. The Representation of Indian Bodies in Nineteenth-Century American Anthropology. In Repatriation Reader: Who Owns American Indian Remains? Edited by Devon A. Mihesuah, pp. 19-36. University of Nebraska Press, Lincoln.

[iii] Williams, Lucy Fowler. 2016. Finding Their Way Home: Twenty-Five Years of NAGPRA at the Penn Museum. Expedition Magazine 58(1): n. pag. Penn Museum, 2016 Web. 23 Nov 2020 http://www.penn.museum/sites/expedition/?p=23604.

Further Reading:

Chari, Sangita and Jaime M.N. Lavallee (eds). 2013. Accomplishing NAGPRA: Perspectives on the Intent, Impact, and Future of the Native American Graves Protection and Repatriation Act. Oregon State University Press: Corvallis.

Colwell, Chip. 2017. Plundered Skulls and Stolen Spirits: Inside the Fight to Reclaim Native American’s Culture. University of Chicago Press.

Mihesuah, Devon A (ed.). 2000. Repatriation Reader: Who Owns American Indian Remains? University of Nebraska Press, Lincoln.

Trope, Jack F. and Walter R. Echo-Hawk. 1992. The Native American Graves Protection and Repatriation Act: Background and Legislative History. Arizona State Law Journal 24:35-78.